History of The Old House (HT)

With thanks to Rochford District Council for supplying images, information and a video file of the restoration.

Press this YouTube link to hear about the restoration of this ancient building.

The Old House is a Grade II listed building.

Until about 1180, most dwellings in England were constructed by banging upright wooden poles into the ground at intervals to form a frame for the walls. These were then infilled with wattle and daub. Wattle was made by weaving thin branches or slats between the poles to form a woven lattice. Daub was made by mixing mud, sand, clay, straw and animal dung together to form a sticky paste which was used to fill in all the spaces in the wattle. Once it dried, the wattle and daub formed the substance of the walls and kept the weather out. The problem was that the posts were put untreated into the ground and within a few decades, the bottom of the posts in the ground would rot away and the building would collapse. This is why so few dwellings of this type from this period survive.

From 1180 onwards, a technical revolution took place. A stone plinth and timber sill at the bottom of walls was introduced. The stone plinth consisted of a row of adjacent stones. On top of this was laid a rectangular wooden beam or sill, usually made of oak. The upright posts, which were also rectangular and made of oak, were attached to this by mortice and tenon joints using oak pegs. Iron pegs were rarely used as it was expensive and the acid in the oak could rot it.

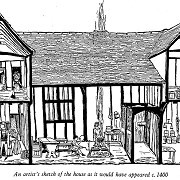

There were then various methods of constructing the walls to keep them upright and provide support for the roof. The Old House is an example of a "fully framed" or "box framed" building. This method of construction usually led to a building that was about 15 feet wide and multiples of 15 feet long. The Old House conforms to this.

The upright posts were placed along the sill to form the structure of the walls. Horizontal beams and curved or straight diagonals were put between the uprights to provide extra strength and the gaps were infilled with wattle and daub. The beams and wattle and daub panels would then be white washed or plastered to make it look more attractive and also to weather proof it.

The Old House was plastered with a mixture of goat hair and lime. The practice of painting beams black was not introduced until the 19th century. The wattle panels were quite easy to break through to gain illegal access to the building and this is where the phrase "breaking and entering" comes from. The wattle and daub used in the Old House contains shells, which can be seen inside in exposed sections preserved behind glass.

Cross beams were erected between the top of the vertical walls and on top of this, the framework for the gable ended pitched roof was constructed. This was then thatched or tiled depending on the locality. From the pitch of the roof and the chimney construction, it can be deduced that the Old House was thatched originally. This was later replaced by burnt clay tiles when they became fashionable.

The Old House is believed to have been built in 1270. A coin dated to between 1216 and 1272 was found in its foundations during restoration works in the 1980s. A ditch dating to the mid-13th century at the front of the building was also found during the restoration.

This would make the house contemporary with the founding of the town around the market, which was established in the middle of the 13th century. There is no evidence of settlement in the current town centre area of Rochford before the establishment of the market, although the current routes of South Street, West Street and North Street may date back to Roman times. The settlement that is mentioned in the Domesday Book was probably located closer to Rochford Hall.

However, the building style of its original hall, now known as The Old Hall, which is the oldest part of the building and now forms the centre room of the building between the two crosswings, is more in keeping with medieval halls from the 1350s. The coin may of course have been in circulation a long while before being placed in the foundations. Radiocarbon dating of timber from the cross hall gives 1350 plus or minus 85 years which gives a date of about 1300. If the 1270 date is correct, it makes it the oldest surviving building in Rochford. If 1350 is correct, King’s Hill in East Street may be older. On balance, despite the building style issue, the 1270 date seems most likely.

Originally the Old Hall had a tiled central hearth in the floor, which was found during the restoration work. This can still be seen under a glass panel in the floor. There was no chimney so the interior would have been smoky, as the smoke had to go up to the roof to find its own way out through the eaves and tiles. The roof timbers are still sooted from this.

Originally there would have been a large full-height window at front and rear. These were not glazed but consisted of solid oak mullions wedged into the frame as vertical bars, with internal shutters to give protection from the weather. Mullions still remain in some rooms but the one at the front was replaced with a bay window in the 15th or 16th century. Before the crosswings were added, the owner of the house and his family would probably have eaten at the north end of the Old Hall, possibly on a raised platform, and would have also slept there. Any servants would have eaten and slept along the floor.

Animals would have been kept in here in the winter too. The floor, now brick, would have been earth and rushes. There was an entrance hall or lobby on the South side of the Old Hall, which linked the front and rear doors. This still exists with the back half still as a corridor but the front half has been incorporated along with the original front door into the downstairs front room of the South crosswing.

A magnificent brick fire place and chimney was added sometime between 1480 and 1530 when chimneys were first introduced. Radiocarbon dating of its timber mantle gives 1440 plus or minus 80 years. Fire places and chimneys were status symbols due to brick being expensive. The bigger your fire place and the taller your chimney, the wealthier you were perceived to be. They also allowed ceilings and first floors to be added as the smoke was no longer a problem since the old hearth was no longer used. This allowed the Old Hall to have a first floor inserted in the late 16th or early 17th century. This has since been removed, but where it was can still be seen by looking at the wall timbers.

Most of the bricks in the fireplace are the original ones, although the hearth front had to be repointed during the restoration in the 1980s. There is a small bricked-in archway on the east side of the fireplace in line with rear door. This was to enable whole logs to be pushed through the back door and through this arch into the fire. The fireplace has witches marks on it to stop them coming down the chimney. Just inside the chimney are some hooks. These were used to hang meat above the fire so it could be cooked.

There are three arches above the fireplace which were probably for a painting, but no traces of any painting have been found. One of the reasons for this is that when the first floor was inserted, the chimney above the fire place was hidden behind wooden panelling, hiding it and the painting arches until the restoration in 1983.

The chimney from the fireplace was widened in its south side to add a second flue at some point in the past. This can be seen on the outside of the building by looking at the chimney from across the road which has additional brickwork in a brighter red on its South side. This may have been for a fireplace in the entrance lobby or the front room of the south crosswing, but there is no evidence of this now.

The north crosswing was added around 1290 as a two storey extension. It became the master’s lodgings. The servants would have continued to live in the main hall. There is a door in in the North wall of the Old Hall which would have given access into the front downstairs room of the north crosswing. It is no longer used. The ceilings in the north crosswing are quite low as people were shorter then. The rear downstairs room has the only medieval window to survive as it was bricked up. It was restored in 1983 when its mullions were replaced. The upstairs front room was the Solar and in medieval times would have been where the master would have relaxed and entertained guests. The upstairs back room in the north crosswing was the master’s bedroom.

In the 18thcentury, a central brick chimney stack was inserted into the North wing. This allowed fireplaces to be added to the rooms on both floors of the wing. The back room on the ground floor may have had one, but this room has now been partitioned where this might have been to provide a toilet, so if there was a fireplace it has now gone.

The downstairs front room of the north crosswing was believed to be a shop in medieval times. The fireplace in the downstairs front room has a cavity either side of it. The left hand side one was an oven and the right hand side one was used to store salt and spices. There was a shelf above the fireplace and burn marks from candles placed upon it can still be seen.

A south crosswing, probably used as a service wing and servant quarters, is believed to have been added around 1390 and the servants would have moved from the Main Hall into it. This has now gone as the current south crosswing dates from the 15th century. It could be it replaced the earlier wing which may have collapsed, burnt down or simply have become unfit for the purposes it was needed for. It may have simply been rebuilt as part of the updating of the house that took place around this time,

The downstairs front room was originally the buttery (for wet goods), the equivalent to a kitchen. The upstairs front room would have been servants’ quarters. The upstairs rear room would have been the room of a higher ranking servant. The rear downstairs room has now been divided into an office, kitchen and toilets. It now sits at the end of the rear corridor which was added, along with the two staircases to the upper floors of the crosswings, in the 18th century. Before that, access to the first floors would have been by ladder. The addition of the rear corridor rendered the door in the north wall of the Old Hall obsolete. The toilets and kitchen are accessed externally. The rear of the south crosswing has another chimney stack to serve its two rear rooms.

The Old House was a high status building for its time. It is not known who built the Old House or who its early inhabitants were. It probably did not belong to nobility, but to a merchant involved with the nearby market or to a landowner as they tended to live in town rather than out on their land. It was probably the case then in South Street that the nearer you get to the crossroads, the higher the status of the buildings become. It was one of a row of such houses built along this side of the road.

By the 1980s, the building was in poor repair and on the point of ruin, so Rochford District Council bought it in 1982 and restored it to use as offices in 1982-3. This was when the hearth and other archaeology was found. Some of the timbers had to be replaced and this was done with century old timbers from a demolished wharf in the Maldon area. These have not been painted so they can be distinguished from the original beams.

The upstairs floor of the front room in the south crosswing was 18” higher than it is now. This is because the original floor was in such bad condition the owners simply put another floor above it. The other upstairs floors are original. The Old Hall was given a new brick floor.

It was decided to use it as offices by the council and it formed part of the Rochford District Council office complex which runs from No. 3 to No. 19 South Street. By the first decade of the 21st century, information technology networks, Wi-Fi, microwave links and fibre optics were added to this ancient building. Rochford District Council reduced its work force size from 2014 onwards and by 2017 no longer needed it as office space. There are now plans to use it for weddings, heritage and other events so the story of this amazing medieval survivor continues.